|

||||

| Dance Me to My Song by Evan Williams The Australian AUDIENCES in Adelaide have been accorded the modest privilege of being allowed to see Dance Me To My Song a week before the rest of us; they should seize the opportunity. Financed by the South Australian Film Corporation, Rolf de Heer's marvellous film was shot in Adelaide, as were his other successes The Quiet Room and Bad Boy Bubby. The Quiet Room and Dance Me To My Song were selected for competition in Cannes. Heather Rose, the cerebral palsy sufferer who stars in Dance Me To My Song, was in Cannes for this year's screening, and I can still see her on the steps of the Palais, cradled in the arms of her co-star John Brumpton, beaming to the crowd and looking terrific in a blue satin number with off-the-shoulder neckline. A more genuinely warm and delighted reception from that notoriously cynical crowd is difficult to recall; and it wasn't just the Australians who were cheering. Later I wondered if the image of that ecstatic moment had coloured my opinion of the film, but I needn't have worried. At a second viewing in Sydney it looked as brave and exhilarating as ever, possessing all the passion of Shine with none of the phoniness and pretension. But its weaknesses could be seen more clearly. Surely no professional carer could be as diabolically unfeeling as the ghastly Madelaine (played by Joey Kennedy), and yes, there are times when the story is hard to believe – though this may simply mean that the unbelievable is more wonderful when it happens.

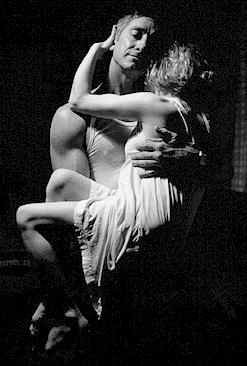

In the evenings, it is Madelaine's habit to make herself comfortable in Julia's house, to which a boyfriend is occasionally admitted; as a special treat, Julia's wheelchair is positioned near the bedroom door so she can observe the lovemaking ("you can watch, but you have to shut up"). That Julia hungers for love and companionship in these surroundings is hardly surprising; what is surprising is the way she goes about finding it. Eddie appears one day in the street, a

passer-by – cool, unassertively good looking, with a nonchalant and taciturn humour.

Julia, on the footpath, blocks his way with her wheelchair. There's some dodging about and

a cautious exchange of glances; As Eddie, Brumpton manages to suggest that he is driven by something more than pity or natural tender-heartedness. It is in some ways the most difficult part in the film. But Rose is the shining centre of the story; there is mischief in those looks, an impish greed in her love for Eddie that gives a kind of playfulness to those painfully contorted movements. Her eyes speak for her: the few pitiful syllables coaxed from her computer are more like subtitles for the audience than words for Eddie. A repeated grunting – sometimes more of a snarl – punctuates her exertions. It's a sound so rhythmic and primal that I wondered if it was Rose's natural voice or a sound effect – like the sinister collage of humming and throbbing David Lynch used for The Elephant Man. Yet in Julia even these minimal sounds take on a natural expressiveness. The weaknesses lie in the other characters – a Madelaine too hateful to be believed (mainly the fault of the writing) and a lesbian chum with a heart of gold (Rena Owen), the only seriously sentimental touch in the film. With Dance Me To My Song, de Heer has broken new ground for the familiar "disability" picture. He has reversed the normal perspective of the viewer. In most of these films – Gil Brierley's Annie's Coming Out is the best comparison – it is the carer's viewpoint that matters: Will Angela Punch McGregor break through to Annie's cloistered disabled soul? In de Heer's film we see the story through Julia's eyes. It is Julia who is struggling to break through, to reach the world beyond herself. And not without some wonder and embarrassment, we identify with her. It is a difficult feat to bring off; and because we are forced to get close to Julia – in a sense to become her – many will find this good and brave film more than they can bear. But stay with it to the end: the rewards are rich indeed. |

Julia heads him off again. At first this behaviour

seems more perverse than flirtatious, but Eddie is persuaded – he is curious, after

all – to follow her into the house. Conversation via synthesiser is marked by some

playful banter; Eddie, too, finds himself saddled with toilet duties, and the mood is the

opposite of romantic. But the development of this unlikely friendship, its fitful and

prankish progress towards genuine attachment and mutual respect, is the central miracle of

the film. And what follows is largely predictable – Eddie's seduction, the jealous

and uncomprehending fury of Madelaine's reaction, her determination to get Eddie for

herself. The outcome will come as no surprise to viewers of inspirational movies, but de

Heer preserves the freshness and integrity of his subject matter with a steely control,

leading us to a truly exultant final scene.

Julia heads him off again. At first this behaviour

seems more perverse than flirtatious, but Eddie is persuaded – he is curious, after

all – to follow her into the house. Conversation via synthesiser is marked by some

playful banter; Eddie, too, finds himself saddled with toilet duties, and the mood is the

opposite of romantic. But the development of this unlikely friendship, its fitful and

prankish progress towards genuine attachment and mutual respect, is the central miracle of

the film. And what follows is largely predictable – Eddie's seduction, the jealous

and uncomprehending fury of Madelaine's reaction, her determination to get Eddie for

herself. The outcome will come as no surprise to viewers of inspirational movies, but de

Heer preserves the freshness and integrity of his subject matter with a steely control,

leading us to a truly exultant final scene.