|

|

|

|

|

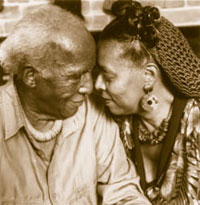

Howard Armstrong & Barbara Ward

|

Louie Bluie

It was back in 1970 when the Earl called me up and said I should be at his bar on Monday night because he had something special, a band called Martin, Bogan and the Armstrongs. "Don't ask any questions," he said. "Just be here." I was there, and I returned week after week for more than a year, along with a loyal cult who packed the place. Martin, Bogan and one of the Armstrongs were black men in their 60s and 70s (the other Armstrong, a son, played bass). They looked like a blues band, but they didn't play the blues, and in fact it was hard to figure out exactly what they did play. They did all the Mills Brothers standards, such as "Lazy River" and "Paper Doll," and they sang "Lady Be Good" and an unprintable version of "Sweet Georgia Brown." Howard Armstrong stood up and did fiddle solos on songs such as "Turkey in the Straw," and brought the house down. |

Howard Armstrong |

|

|

Sixteen years later, those Monday sessions blur into a smoky series of hot summer nights when the sweet lyrics of Armstrong's fiddle danced above Martin's guitar and Bogan's mandolin, and they took turns on the vocals, including Martin's composition of "The Barnyard Dance" and Armstrong's pseudo-Hawaiian love songs. Toward the end of the evening, Ted Bogan would sing "Summertime" with such unadorned purity that you knew, quite simply, that you would never, ever, hear that great song sung better by anyone, anywhere. Martin, Bogan and the Armstrongs stopped playing together in the mid-1970s, and a few years later the Earl of Old Town closed its doors. When I would run into Earl Pionke, I would ask him about them and he would have vague reports that they were in Detroit, or Tennessee. Then word came that Carl Martin, who always scowled the fiercest when he was singing the funniest lyrics, had died. And that was the situation last Labor Day when I went to the Telluride Film Festival, up in the San Juan range of the Rockies, and there on Main Street I saw Howard Armstrong with his beret and all that hip jewelry around his neck, checking out the scene and giving free advice to Ted Bogan, who was nodding and not listening, just like he always did when Armstrong talked to him during the sets at the Earl. The story of how they got to Telluride is an amazing one, and it explains the existence of "Louie Bluie," an equally amazing music documentary film. Terry Zwigoff, a music lover who went on to produce and direct "Louie Bluie," was an avid collector of old jazz and blues recordings. He liked the sound on an old 1930s disk that was by somebody named Louie Bluie who never recorded before or since, and after years of searching he found out that Louie Bluie was Howard Armstrong, and his group, one of the first (and now one of the last) of the traditional black string bands, was still around. |

|

|

|

Zwigoff tracked down Armstrong, who had moved to Detroit, and talked Armstrong and Bogan into appearing in a film, and "Louie Bluie" is that film, filled with music and life and humor, but also with an extraordinary portrait of Howard Armstrong, who is an artist, poet, composer, violin virtuoso, storyteller and tireless womanizer (according to many of his stories). The movie is loose and disjointed, and makes little effort to be a documentary about anything. Mostly, it just follows Armstrong around as he plays music with Bogan, visits his Tennessee childhood home, and philosophizes on music, love and life. The film occasionally turns to the pages of the semi-pornographic journals Armstrong has kept through the years, filled with lurid cartoons and bawdy poems and his observations on life. (The journals will be published later this year, having been embraced by devotees of pop art.) Armstrong is a natural artist, and he remembers making his first colors out of dyes wrung out of crepe papier. There is a lot of music in the movie, including some I could do without. (Armstrong likes his Hawaiian and German songs much better than I do.) There is also an enigma to consider: the relationship of Bogan and Armstrong, who have known each other and played together for almost 70 years, despite the fact that Armstrong is almost always on Bogan's case, and Bogan's eyes always seem to be looking for the nearest exit. "Louie Bluie" peers into the areas where nothing is certain, except that these people live and strive and laugh and make music. It is a wonderful film. |

|