MISHIMA: A LIFE IN FOUR

CHAPTERS

|

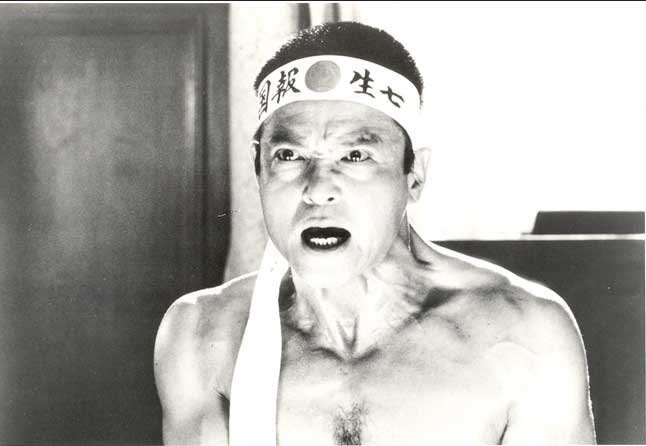

By Roger Ebert Paul Schrader's "Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters" (1985) is the most unconventional biopic I've ever seen, and one of the best. In a triumph of concise writing and construction, it considers three crucial aspects of the life of the Japanese author Yukio Mishima (1925-1970). In black and white, we see formative scenes from his earlier years. In brilliant colors we see events from three of his most famous novels. And in realistic color we see the last day of his life. What he did on that day validated, in his mind, both his life and his work. A fanatic traditionalist who exalted the medieval code of the samurai, he had formed a private army to express his devotion to the emperor. With four of its members, he drove to a regimental headquarters of the Japanese army, held a general as hostage, demanded to be allowed to address the gathered troops, and then committed ritual suicide by simultaneously disemboweling himself and having an acolyte behead him. As unorthodox as Schrader's approach to Mishima's life may be, I cannot imagine a better one. Like Hemingway and Mailer, Mishima conceived his life and his work as intimately related through his libido. In Mishima's case this process was made more complex by his bisexuality and masochism, and his "private army" combined ritual with buried sexuality; his soldiers were young, handsome and willing to die for him, and they wore uniforms as fetishistic as the Nazis. Schrader has throughout his life as a screenwriter and director been fascinated by the starting-point of a "man in a room," as he describes it: a man dressing and preparing himself to go out and do battle for his goals. In his screenplays for Scorsese's "Taxi Driver" and "Raging Bull," great emphasis is placed on Travis Bickle and Jake LaMotta preparing for conflict, Bickle with his elaborate gun mounts and verbal rehearsals, LaMotta in his dressing room. In Schrader's own "American Gigolo," his hero trains and dresses himself to seem attractive to women, and in his latest film, "The Walker," he shows a man carefully preparing to be a presentable companion for older women. |

|

Mishima is his ultimate man in a room. There is the young boy, separated from his mother and held almost captive by a possessive grandmother, who won't let him go out to play but wants him always at her side. There is the writer, returning to his desk every day at midnight to write his books and plays in monkish isolation. There is the public man, uniformed, advocating the Bushido Code, acting the role of military commander of his own army. On the last day of his life, he is ceremoniously dressed by a follower and adheres to a rigid timetable that leads to his meticulously planned and rehearsed suicide, or seppuku. Considering that he is a man fully committed to plunging a sword into his own guts, he seems remarkably serene; his life, his work, his obsession have finally become synchronous. He is insane, yes, but not confused. He thinks with the perfect clarity of the true believer, and in this case his belief is in himself and his statement. His desire is to provoke an army mutiny that will overthrow democracy and other Western infections, and restore the supreme power of the emperor. Not even the emperor agrees with him, but such is Mishima's overwhelming charisma that his army recruits want to join him in death. Schrader contrasts this adult martinet with the shy sissy whose grandmother warned him he would get sick if he went outside. As a boy, Mishima was afflicted with a paralyzing stutter, was weakly, was the target of bullies. The film's biographical sequences show him being advised by a friend who limps to exploit his own disability as a way of making himself attractive to women. Eventually these lessons take a turn: Mishima becomes a muscular body-builder, a paragon of surface masculinity, to attract men -- not so much as his lovers but as his followers or slaves. Their worship validates his supremacy and denies his deep-seated feelings of inferiority. These scenes from his life find mirrors in the sequences inspired by three of his novels, Temple of the Golden Pavilion, Kyoko's House and Runaway Horses. These scenes, shot on a sound stage at Tokyo's Toho Studios, are remarkably stylized, and filmed in rich basic colors. The production design is by Eiko Ishioka, who was honored at Cannes for her work on this film, won an Oscar for Coppola's "Dracula," designed "M. Butterfly" on Broadway and the "Varakai" production for Cirque du Soleil in Las Vegas and created the extraordinary visuals for Tarsem Singh's "The Cell" (2002). Temple of the Golden Pavilion involves a young monk at an ancient temple, who is overcome by its beauty and burns it down. The story is inspired by actual events in 1950. Ishioka's sets of dazzling red and gold include collapsing walls that open before the monk vagina-like. Kyoko's House is based on a 1959 novel that turned out to be prophetically autobiographical. Its hero, a body-building boxer, commits suicide with his lover. Runaway Horses is about a young man in the early 1930s who leads a plot to assassinate government figures and restore the emperor. In one way or another, all three prefigure events in Mishima's life; the first, about the destruction of beauty, connects with his belief that a man should grow steadily more beautiful until the age of 40, when he has reached perfection and should die before decay sets in. The title character is played as an adult by Ken Ogata ("Vengeance is Mine," "The Pillow Book"), who portrays the character without signaling or spin; his Mishima is self-contained, reticent, confident. Only in a voice-over does he betray his uncertainties. What we see in the "present" is essentially the persona he so elaborately created, and it is easy to think of Norman Mailer stepping into the boxing ring, running for office, head-butting Gore Vidal, stabbing a wife. The public actions somehow lend weight to the writing. The screenplay was written by Schrader in collaboration with his brother Leonard (1943-2006), who lived, taught and married in Japan and also wrote "Kiss of the Spider Woman" and collaborated with Paul on "The Yakuza" (1975). The Japanese dialog was co-written by Leonard's wife, Chieko. If you were to stand back and look at the mismatched facts of Mishima's childhood and adult years, and then consider the bewildering profusion of his novels, stories, plays, Noh dramas, public behavior, film acting and self-promotion, you might despair of assembling it into a coherent screenplay. The unconventional structure of the film might seem to lead to confusion or distraction, but actually it unfolds with perfect clarity, the logic revealing itself. |

|

Schrader, born 1946, is one of the most intelligent and fascinating figures in contemporary film. A key to his work may be his 1972 book Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer), in which he values those directors above all others. It may seem impossible to reconcile their aesthetics with the frequent violence and sex of his work, but at a deeper level few filmmakers are more concerned with the morality of the characters. His films are often about life choices and compulsions and how they work out in real life and have unintended consequences. They spring directly out of his fundamentalist upbringing in Grand Rapids, where he had values so deeply imprinted that they have expressed themselves, however indirectly, ever since. That made him doubly sympathetic to the deep-rooted Catholicism of his lifelong collaborator Scorsese. I remember a night after the premiere of "Mishima," a competitor for the Palme d'Or at Cannes in 1985. The film was well-received, and won an overall award for "best artistic contribution" (by Ishioka, cinematographer John Bailey and Philip Glass, for one of his best scores). But Paul knew better than anyone that its chances at the American box office were slim. We met at a backstreet Japanese restaurant, where he observed that his co-producers, Francis Coppola and George Lucas, had raised $10 million "with no hope of getting it back," and indeed the film grossed only about $500,000 in the U.S. "This may have been my last film," Schrader said, and that's also something I've heard more than once from Scorsese. It is Schrader's problem, and also his gift, to make films he believes in. Some are deeper, some entertainments, but none are merely jobs of work. He must have found Mishima's headlong dedication to his art a powerful attraction.

Cast & Credits A film by Paul Schrader. Written by Leonard Schrader, Paul Schrader and Chieko Schrader. Starring Ken Ogata, Masayuki Shionoya, Junkichi Orimoto. Music by Philip Glass. In Japanese, with off-screen English narration. Rated R. Running time 121 minutes. |