CITIZEN KANE (with Roger Ebert commentary track)

By Roger Ebert / May 24, 1998

RELEASE DATE: 1941

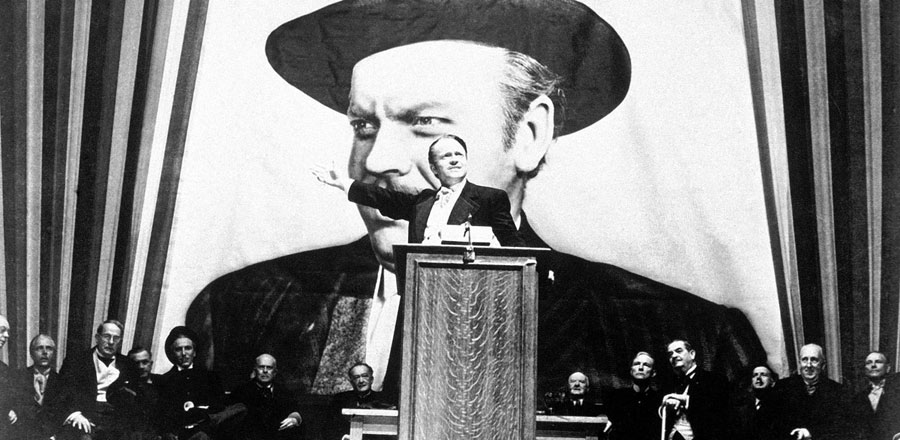

I assume every Ebertfest audience member has seen Citizen Kane at least once, perhaps many times. I'm including it in this year's Ebertfest for a personal reason. I recorded the video commentary track for the DVD, and it has been retained in the magnificently restored new 70th anniversary edition of the film from Warner Bros., released last autumn. The track had some success, and was named commentary of the year by Variety. The last year I was able to speak was at Ebertfest 2006. So Ebertfest 2012 is also an anniversary of sorts, and it occurred to me to present the film with the commentary track, so that one more time my voice can be heard in this lovely theater.

"I don't think any word can explain a man's life," says one of the searchers through the warehouse of treasures left behind by Charles Foster Kane. Then we get the famous series of shots leading to the closeup of the word "Rosebud" on a sled that has been tossed into a furnace, its paint curling in the flames. We remember that this was Kane's childhood sled, taken from him as he was torn from his family and sent east to boarding school.

Rosebud is the emblem of the security, hope and innocence of childhood, which a man can spend his life seeking to regain. It is the green light at the end of Gatsby's pier; the leopard atop Kilimanjaro, seeking nobody knows what; the bone tossed into the air in 2001. It is that yearning after transience that adults learn to suppress. "Maybe Rosebud was something he couldn't get, or something he lost," says Thompson, the reporter assigned to the puzzle of Kane's dying word. "Anyway, it wouldn't have explained anything." True, it explains nothing, but it is remarkably satisfactory as a demonstration that nothing can be explained. Citizen Kane likes playful paradoxes like that. Its surface is as much fun as any movie ever made. Its depths surpass understanding. I have analyzed it a shot at a time with more than 30 groups, and together we have seen, I believe, pretty much everything that is there on the screen. The more clearly I can see its physical manifestation, the more I am stirred by its mystery.

It is one of the miracles of cinema that in 1941 a first-time director; a cynical, hard-drinking writer; an innovative cinematographer, and a group of New York stage and radio actors were given the keys to a studio and total control, and made a masterpiece. Citizen Kane is more than a great movie; it is a gathering of all the lessons of the emerging era of sound, just as Birth of a Nation assembled everything learned at the summit of the silent era, and 2001 pointed the way beyond narrative. These peaks stand above all the others.

The origins of Citizen Kane are well known. Orson Welles, the boy wonder of radio and stage, was given freedom by RKO Radio Pictures to make any picture he wished. Herman Mankiewicz, an experienced screenwriter, collaborated with him on a screenplay originally called "The American". Its inspiration was the life of William Randolph Hearst, who had put together an empire of newspapers, radio stations, magazines and news services, and then built to himself the flamboyant monument of San Simeon, a castle furnished by rummaging the remains of nations. Hearst was Ted Turner, Rupert Murdoch and Bill Gates rolled up into an enigma.